On the surface, the friendship of Myles Horton and Septima Clark would seem to have been impossible. He was born in Savanna, Tennessee in 1905. She was born in 1898 in Charleston, S.C. He was a highly educated white man with an undergraduate degree, followed by a degree from Union Theological Seminary in New York City, then a Ph.D. from the University of Chicago. Septima learned to read and write from an elderly white woman who privately tutored Black children. As there was no public school for Blacks beyond 6th grade, Septima attended Avery Institute, an academy for Black students founded by missionaries from Massachusetts. After graduation from Fiske University, she passed a state certification exam which permitted her to teach, but only in rural Black schools.

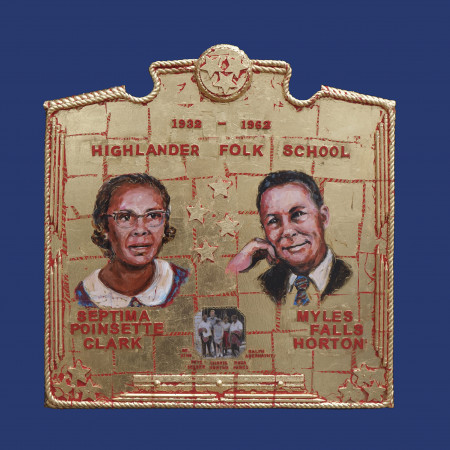

After spending time with the social reformer Jane Addams at Hull House in Chicago, Horton traveled to Denmark to explore the Danish Folk School model of education and learned of the way that its educational practices had addressed the social and economic upheavals there in the 1890s. He admired the informality, the close student-teacher interaction, and the use of the culture of a local community as a tool for learning and social change. Here he began to think of ways to apply this educational philosophy to the people of his own region in the U.S. When he returned home in 1932 he rented a small farm on a mountain top in Monteagle, Tennessee and established the Highlander Folk School as an educational institution for the poor and working people of Appalachia. The school continued through the early 1960s when the state revoked its license in retaliation for its civil rights activities.

During these same years, Septima Poinsette was beginning her career as a teacher in rural South Carolina. Soon, however, she returned to Avery as an instructor and engaged in a variety of educational reform activities. She became instrumental in the movement for Blacks to teach in Charleston. She was married to Nerie Clark who died of kidney failure in 1925. She then moved to Columbia,

S.C. to continue teaching and there she helped organize a branch of the NAACP. She collaborated with Thurgood Marshall on a landmark case that sought equal pay for Black and white teachers. In the mid-1950s South Caro- lina passed a law making it illegal for a public employee to be a member of a civil rights organization. She refused to give up her membership in the NAACP and lost her job.

What brought Myles Horton and Septima Poinsette Clark together was their shared philosophy in using education as a method to activate voter registration among the Black population – as well as other forms of non-violent civil rights actions. They met for the first time at a teacher’s conference in Tennessee, after Septima was forced from teaching in S.C. Horton invited her to join the Highlander staff. By now the Highlander Folk School was fully committed to the training of Civil Rights Movement activists. Early on the School had focused on developing ways for the poor and unemployed to organize labor unions. It fought segregation in the labor movement, holding its first integrated workshop in 1944. Its commitment to ending segregation made it a natural place for training civil rights activists. The basis was laid here for the Montgomery Bus Boycott, the founding of SNCC, and the Citizen Schools. Poinsette Clark was co-architect with Horton of the Citizen Schools which taught disenfranchised Blacks to read and write, thus enabling them to register to vote. This model was used throughout the South during the 1950s and ‘60s and was the basis for Freedom Summer in 1964 which brought Black and white college students from around the country to encourage voter registration and out of which the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party was formed.