Icons in the Struggle for Racial Equality

Icons in the Struggle for Racial Equality

In Greenwich, Art Focusing on Civil Rights Figures

By Clay Risen Feb

One day in the summer of 1955, when the artist Pamela Chatterton-Purdy was 15 years old, her father got a call from Jackie Robinson, the Brooklyn Dodgers’ second baseman and the first black man to play Major League Baseball in the modern era. Robinson was planning to buy a home in North Stamford, Conn., near where her family lived, and he wanted to hire her father’s van company for the move.

Her father said yes — and almost immediately, anonymous callers were ringing the family’s phone at all hours, threatening him and his children if he dared to help a black man, even a world-famous baseball player like Robinson, move to their town.

“They said, ‘Mr. Chatterton, do you care about the health of your four daughters?’ ” said Ms. Chatterton-Purdy, now 74. “We were all shocked, and needless to say, Dad was not to be bullied.” Her father went through with the move.

Still, that memory, and her later experience as one of the few white employees at Ebony magazine in Chicago, have motivated much of Ms. Chatterton-Purdy’s artistic career. Her current project, a series of mixed-media icons commemorating the civil rights movement, is the subject of an exhibition at Les Beaux Arts Gallery, in Round Hill Community Church in Greenwich, which opened Feb. 1 and runs through the end of March.

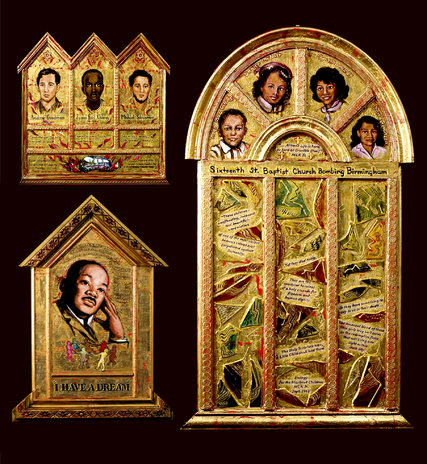

Like the Eastern Orthodox Church panels that inspired her series, each of the 30 icons on display consists of a gilded wooden frame built around a portrait of a civil rights figure: familiar names like the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks and those less well-known, like Jimmie Lee Jackson, an activist who was shot and killed by a state trooper in 1965 during a protest march in Marion, Ala., while trying to defend his mother from another trooper’s nightstick.

Many of Ms. Chatterton-Purdy’s works focus on civil rights figures from the South, but she has also painted several icons of Northern activists who went south to join the fight for equality, including several who died doing so. Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner, for instance, both from New York, were murdered in Mississippi in 1964, along with James Chaney, a native of Meridian, Miss.

In another nod to iconic tradition, Ms. Chatterton-Purdy loads her works with symbolism: Her icon of Emmett Till is framed by 14-inch rulers, marking his age when, in 1955, he was beaten and murdered by two men in Money, Miss., who accused him of whistling at a white woman.

Ms. Chatterton-Purdy, who lives with her husband, David, a retired minister, in Harwich Port, Mass., began thinking about the series after taking a trip in 2004 through the Deep South to visit sites related to the civil rights movement. During a stop in Birmingham, Ala., she met Chris McNair, a former lawmaker whose 11-year-old daughter, Denise, was one of four girls killed by a Klan bomb in 1963 at the 16th Street Baptist Church. Ms. Chatterton-Purdy gave him a poster she had designed for Ebony in the aftermath of the tragedy.

“I learned so much about civil rights that I didn’t know, and I decided art could help remind people about what the movement meant,” she said.

She began the project in 2007, and while her early icons focused on individuals, at her husband’s suggestion she began to create works dedicated to events, like the Freedom Rides and Bloody Sunday in Selma, Ala., and to themes, like women in the movement.

With the recent spike in activism after the killing of unarmed black men in Missouri and Staten Island, as well as the debut of the film “Selma,” the show’s timing is propitious.

And interest in the works is growing: While she continues to add to the series, Ms. Chatterton-Purdy said these days she spends most of her time moving the bulky collection from gallery to gallery around New England.

When the current show closes, she will drive back to Greenwich, pack the icons into a moving van and drive them to the Historical Society of Cheshire County in Keene, N.H., where her next show will start a few days later. Then, in May, the collection will move to the Zion Union Heritage Museum in Hyannis, Mass.

Indeed, Ms. Chatterton-Purdy said, her schedule is booked solid well into 2016. “I’m just going to keep on going,” she said. “It’s up to the Lord.”

“Icons of the Civil Rights Movement,” by Pamela Chatterton-Purdy, continues through March 31 at Les Beaux Arts Gallery at Round Hill Community Church, 395 Round Hill Road, Greenwich, Conn., Information: roundhillcommunitychurch.org; 203-869-1091.