One of the most influential religious leaders of the 20th Century, Rabbi Abraham Heschel spoke to both Jews and Christians. Born in Warsaw, Poland in 1907, he pursued a doctorate in Germany and received a liberal rabbinic ordination at the Hochschule fur die Wissenschaft des Judentums. In 1938, while living in Frankfurt, he was arrested by the Gestapo and deported to Poland. Six weeks before the German invasion of Poland he left Warsaw for London. Heschel never returned to Germany or Poland. One sister was killed in a German bombing; two others died in concentration camps, and his mother was murdered by the Nazis.

Heschel came to the U.S. in 1940 and served on the Hebrew Union College faculty in Cincinnati. In 1946 he became professor of Jewish Ethics and Mysticism at the Jewish Theological Seminary of America where he taught until his death in 1972.

No doubt, due to his personal experience of persecution under the Nazis, he became a powerful voice for spiritual renewal and social change. Inextricably linking spirituality and social activism, he passionately challenged Jews and Christians to become God’s partners in the creation of a just and compassionate world. During the 1960’s, Heschel marched for civil rights with Martin Luther King and was a leader in the antiVietNam War movement. As King encouraged Heschel’s involvement in the Civil Rights movement, Heschel encouraged King to take a public stance against the war in VietNam. When King was assassinated in 1968, Rabbi Heschel was invited by Mrs. King to speak at her husband’s funeral.

The relationship between Heschel and King began in January 1963 when they met at a Religion and Race conference in Chicago where Heschel gave a major address. Perhaps Rabbi Heschel and Dr. King became allies in the cause of peace and justice as well as close personal friends because they shared a belief in the interconnection of the political and the spiritual. Both spoke about God being deeply involved in the affairs of human history. Social activism was required by people of religious faith, Heschel and King argued, particularly when society had developed immoral institutional structures. Heschel noted: “Your highest loyalty is to God and not to the mores, the folkways, the state or the nation or any human made institution.”

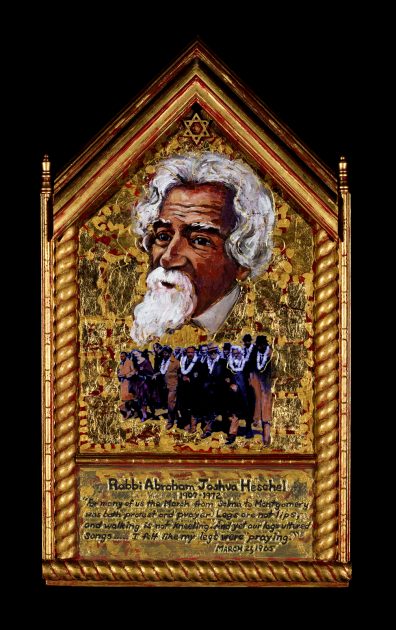

On March 19, 1965, two days before the March from Selma to Montgomery, Heschel received a telegram from King, inviting him to join the march. Heschel was welcomed as one of the leaders into the front row of marchers with Ralph Bunche and Ralph Abernathy. Each of them wore flower leis brought by Hawaiian delegates. For Heschel, mystic and social activist, the march had a powerful significance: “For many of us the march from Selma to Montgomery was about protest and prayer. Legs are not lips and walking is not kneeling. And yet our legs uttered songs. Even without words, our march was worship. I felt my legs were praying.”