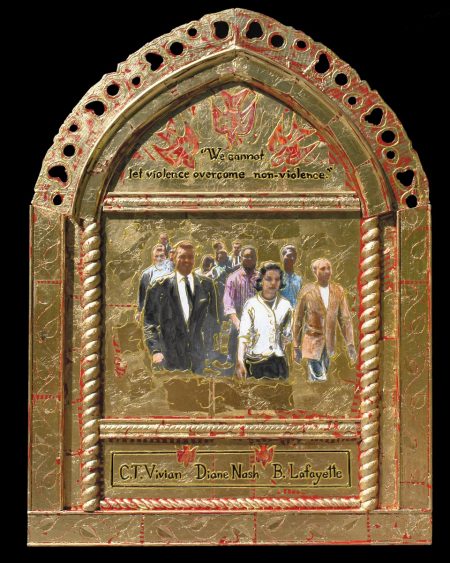

“We cannot allow violence to overcome non-violence…”

C.T. Vivian was several years older than the college students with whom he demonstrated against the Jim Crow laws of Nashville. By all accounts he was intense, outspoken, and confrontational. He was both a minister and a student having come to Nashville from Illinois to study at the American Baptist Seminary. He was pastor of a church, an editor at his denomination’s newspaper and a ministerial student. He had clashed with the forces of segregation from the moment he arrived in 1955. He refused to sit in the back of the bus and insisted on being arrested just at the time the city was negotiating an end of segregated public transportation following the success of the Montgomery bus boycott. For the younger college students who were learning the tactics of non-violence, his mentoring was a powerful influence.

Diane Nash emerged as one of the outstanding civil rights leaders of the 1960’s. Many young women were active in the Civil Rights Movement, but because of her commitment to the practice of non-violent change and her willingness to give her life to the cause, she helped guide the sit-ins in Nashville and the freedom rides throughout the South.

Growing up in Chicago, she spent a year at Howard University in Washington, DC, then transferred to Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee where she was stunned by her experience of segregation. She joined the workshops in non-violent resistance led by the Rev. James Lawson, a graduate student at Vanderbilt University Divinity School. At first hesitant to believe in the effectiveness of non-violence, she soon became a spokesperson for the Nashville sit-ins due to the strength of her commitment and her calm, dignified manner. In the spring of 1960, accompanied by Rev. C.T. Vivian and fellow students Bernard Lafayette, John Lewis, and James Bevel, she led a massive protest march of college students to City Hall. There Nash confronted Mayor Ben West, asking him if it was morally wrong to discriminate on the basis of race. He replied, “Yes”. A few weeks later the lunch counters throughout the city were open to all regardless of skin color.

With students from black colleges and universities throughout the South, Nash was one of the founders of the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee in 1960. A year later, after violent attacks in Alabama threatened the continuation of the Freedom Rides which had been organized by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), she convinced SNCC to sponsor the Rides, knowing that if violence was allowed to stop them, then the whole Civil Rights Movement could fail. John Seigenthaler, a representative of U.S. Attorney General, Robert Kennedy, tried to dissuade her. She understood that students could be injured and even killed. “But”, she said emphatically, “we cannot let violence overcome non-violence.” Furthermore she informed him that the students had already signed their last wills and testaments.

Bernard Lafayette, because of his easy manner and seeming lack of intensity, was a less well known activist than some others who were with him on the front lines of the Movement. Along with John Lewis, Diane Nash, James Bevel, Marion Berry, he was among that core group in Lawons’s workshops on non-violence. An exceptional student in his Tampa high school, he won a full scholarship to Florida A&M to study journalism. But he felt the call to preach and instead enrolled at American Baptist Seminary in Nashville. Lawson’s seminars brought together two of his strongest interests, religion and politics. Thus he became an early participant in the sit-ins. The following year, he had to carefully consider whether he was willing to die as a Freedom Rider. Finally with nineteen others in Nashville, he signed his last will and testament. With many other Freedom Riders, he spent the summer of 1961 in a Mississippi jail.