The Freedom Rides began in the early 1960’s to test Federal court rulings which confirmed equal access to buses and other forms of interstate transportation. In 1955, the Interstate Commerce Commission ruled that blacks had the right to sit with whites on buses when traveling across state lines. A Supreme Court ruling in 1960 declared segregation in interstate bus and railroad stations unconstitutional.

In spite of the law guiding interstate transportation, local laws in most southern locations made it impossible for blacks to exercise their Constitutional rights. When John F. Kennedy was elected president in 1960, he promised to enforce and expand equal rights legislation. For some, he did not act quickly enough on his pledge. In 1961, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) organized the Freedom Rides as a way to challenging discriminatory practices in public transportation. The first Freedom Ride began on May 4, 1961. It was composed of blacks and whites who left Washington DC on Greyhound and Trailway buses. Their plan was to ride throughout the southern states eventually arriving in New Orleans.

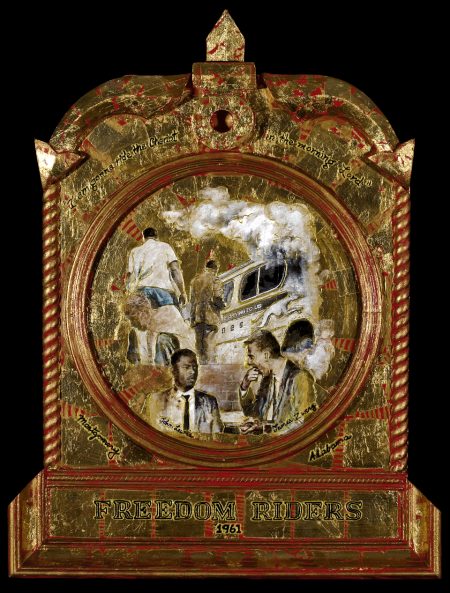

The Freedom Riders never got that far. While encountering little difficulty early in their journey, in Anniston, Alabama, a mob attacked the Greyhound bus and slashed its tires. When the bus was forced to stop a few miles out of town, it was firebombed by a mob organized by the KKK. As the bus burned, the attackers held the doors shut intending to burn the Freedom Riders to death. An exploding fuel tank caused the attackers to retreat and the riders escaped. Only shots fired into the air by police prevented the Riders from being lynched. Taken to a nearby hospital for treatment, a mob gathered outside. Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth, from Birmingham, organized a rescue mission in the middle of the night.

The Trailways bus finally reached Birmingham. When the Riders began to exit the bus they were hit with bats, chains and iron pipes. Whites were particularly singled out for frenzied beatings. Despite the violence already suffered and the threat of more to come, the Freedom Riders desired to continue their journey. More obstacles were encountered when Greyhound drivers refused to continue for fear of more violence upon their arrival in Montgomery. SNCC leader Diane Nash felt if violence was allowed to deter the Freedom Rides, the civil rights movement would be set back. So on May 19, an effort was made to begin again in Birmingham. Under intense pressure from Attorney General Robert Kennedy a driver was provided and Alabama Governor John Patterson promised to protect the bus along the route to Montgomery. However, when the bus reached the city line, the Highway Patrol abandoned them. The Riders were attacked with pipes and chains. John Lewis and James Zwerg were among those bloodied by the attack.

Instead of being intimidated by the violence, the Freedom Rides continued throughout the summer. More people became engaged in other forms of direct action, including voter registration and freedom schools throughout the South, because of the heroic and non-violent action of the Freedom Riders.